Most of us would agree that we learn best through experience—by doing ourselves what we are trying to learn to do. We know that to learn how to do anything, you have to actually do it.

To learn to swim, you have to get in the water, pick up your feet, and move your arms and legs. To learn to ride a bike you have to get on the bike, push off, and pedal.

And honestly, our first tries are usually not pretty. But to learn to do anything, first you must try.

To learn to do anything well, we must practice. A lot. It is practice—doing what we are trying to learn to do—that matters most to developing proficiency—much less expertise—in any domain. Nobody ever got good at anything without doing it.

Yes, learning is often made easier when we have an opportunity to see someone else do whatever we are trying to learn to do. Demonstrations and explanations by more expert others can have a powerful effect on learners and their learning.

But watching someone else cook or play tennis or run or write or play the cello or read or build a circuit or fix a car is not what develops proficiency.

Practice does. You have to do it. And do it. And do it.

And while you are engaged in doing whatever you are learning to do, a bit of coaching—from someone who knows what proficiency looks like and sounds like, who knows how to offer timely, focused, specific feedback, and who can help you to reflect on the moves you are making—can be extremely beneficial to guide learning.

Becoming literate—developing the ability to read, write, speak, listen, and use the language of any physical or intellectual domain—develops through repeated practice, over time. It requires:

- doing whatever you are trying to learn (and being willing to do it badly at first),

- much, much, much practice,

- now and then a helpful demonstration from a more expert other, and

- if you are lucky, thoughtful, timely, and specific coaching from someone who knows what proficiency looks like and sounds like.

Agreed?

So, why is it that we teachers, who say that we learn best by doing, still write lesson plans rather than learning plans? Why do our plans outline what we will say and do rather than planning what students will do and learn how to do in order to learn the way experts learn in our disciplines?

And why is it that when we administrators do observations, our observations focus on teachers’ teaching? Why aren’t our instruments focused on students and what they are doing to in order to learn? After all, these data would reflect on the teacher, as well, because the teacher is the one who causes students to do whatever they are doing. Right?

Perhaps our biggest challenge in HPL is to help educators flip their thinking about planning, teaching, and learning to create learning plans rather than lesson plans, and to create classrooms that are laboratories for learning how to do what we don’t already know how to do, and for developing expertise through practice.

Learning plans need to focus on how students will actively engage in the processes people use to learn in our disciplines.

Learning labs need to be places where students learn to engage in the processes real people use to learn mathematics, science, history, economics, geography, civics—whatever.

Gary Fenstermacher (1986), termed these processes of learning, “studenting,” to set the active “doing” part of learning apart from the outcomes of learning. He explains that teachers should be,

“held accountable for the activities proper to being a student (the task sense of ‘learning’), not the demonstrated acquisition of content by the learner (the achievement sense of ‘learning’).”

In other words, when we teach students how to student in a discipline, we should be able to connect the dots between what they do (and do not do) in order to learn in our disciplines and extent to which they successfully acquire the content in our disciplines. The concept of studenting allows us to connect learning inputs with outcomes, so that when students have difficulty learning content, we can track backwards to their learning processes to provide the help they need to be successful.

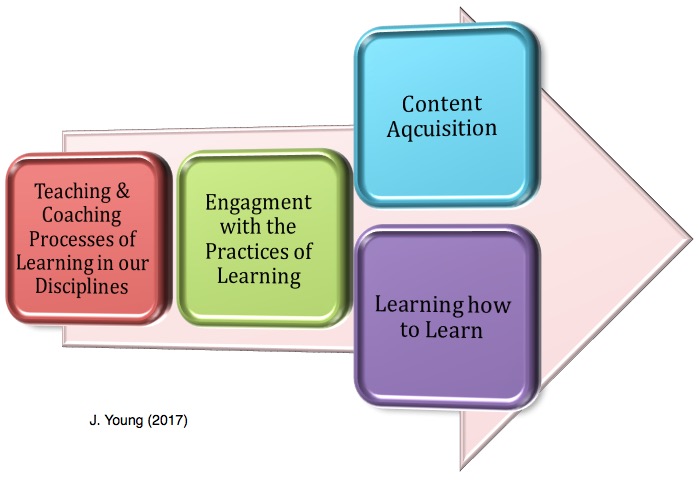

Fenstermacher’s concept of studenting helps us understand how critical it is to teach students how to learn in our disciplines. If we coach them to the point where they are able to independently take over the processes of reading, writing, speaking, listening, and doing in our disciplines, then one successful outcome will be that they acquire the content of our disciplines.

However, the more powerful outcome is the holy grail: they will learn how to learn for a lifetime. And we will have created college- and career-ready graduates.

In our classrooms, we are cause agents.

We plan what happens and what does not happen. We decide how much time we will spend teaching or talking while students listen to us. We decide what they will read and write, when they will read and write, and how much they will read and write. We set the expectations. We establish the routines. We choose whether we will teach routines and procedures to the point of habit or whether we will repeat the same directions for the same things each day and police students to comply. We decide how much time they will have to actually do what they are learning to do. We decide whether kids will practice individually or with a partner or in a collaborative group. We determine whether we will provide small group instruction or one on one instruction while kids are working.

It’s cause and effect.

In future blog posts, we will explore how we plan for and teach studenting—learning how to learn—through what we call The New Norms for Learning in HPL within a Reading-Writing-Research Workshop structure. Stay tuned!

High Progress Literacy is copyright (c) 2022 by High Progress Literacy Associates, LLC. The materials on this site are free for individual use and for educational purposes. Any commercial use is strictly forbidden. Materials may not be redistributed without the express written permission of High Progress Literacy Associates, LLC.

0 Comments